|

During his lifetime, Leonardo "Dada" Vinci was celebrated for his sculptures, paintings and avant-gardens. The "Mono Lisa," a painting of a girlfriend who was stricken with chronic infectious mononucleosis, is so lifelike that the lymph nodes appear to either swell or subside when viewed from certain angles. Equally impressive, every entrée that graces "The Last Supper" features a scratch 'n sniff patch that is still identifiable more than five hundred years after being affixed to the painting. But Leon was also a Certified Scientific Investigator, as the voluminous technical journals that he kept attest. His notes and sketches indicate he was interested in many branches of science, from insect repair to calamitology. They also envisioned future possibilities, such as automats and flying machines. Among the latter were detailed sketches of ornithopters--mechanisms with flapping wings--as well as devices that resemble today's experimental lighter-than-air abattoirs. Discovered only recently hidden amongst Louvre gift shoppe tchotchkes was a sketch for another flying machine called il propellier, or "the propellerizer." It bears a striking resemblance to the modern propeller beanie, in that propeller-like blades are mounted atop a person's head. However, Dada Vinci's design showed the spinning blades actually lifting the person into the air.

Along with il propellier was a sketch for il turban di vento, the wind turban. This invention combined Leon's interest in energy that could be derived from naturally moving air with Moslem headdresses. In theory, a propeller attached perpendicular to the turban connected to a rotor that in turn connected to a shaft. When the wind blew, the propeller turned the rotor that turned the shaft that spun a generator located deep within the cloth windings which, when plugged into a wall socket, created electricity. In a striking example of Dada Vinci combining art and science, his famous painting, "Adoration of the Magi," features vast fleets of men and women with i turbans di vento strapped to their heads soaring nonchalantly through the skies, while the Magi below appear to be consecrating an automat.

In still another meticulously illustrated design, a much larger turban sits atop a windy hill, its twenty-foot blades spinning madly. Centuries later, this drawing became the basis for the first wind cultivation project. The Hobson Wind Ranch was built atop a mountain ridge in Bung Hollow, West Virginia, where the strongest winds on Earth blow. By this time, the turban had evolved into a full-fledged machine with buckets, paddles and blades called a turbine that was no longer worn exclusively as headgear. The Hobson turbines were mounted on towers that faced directly into the wind. Contrary to Dada Vinci's design, this idea proved to be disastrous. On the Ranch's very first day of operation, the wind blew so ferociously that the turbines' blades acted like propellers on a giant airplane, uprooting the turbines and towers as well as thirteen hectares of land and flying the lot off to the north, where they were never seen again.

Dadaologists are split as to whether Leon really thought the large turban idea would fly (ha). Some argue that his abiding interest in calamitology necessitated the occasional disaster. Others point to an even more detailed sketch of an alternative wind farm design as proof that he had abandoned his original plan. The later design employs neither turbines nor generators. Rather, it depicts a farmer planting individual winds on a cultivated plot of land. Dada Vinci's own description calls for the wind rows to be spaced nine to twelve inches apart, with a gap of thirty-six inches between the rows. He postulated that if different winds were mixed in the same field, cross-pollination could occur, resulting in blustery, squally conditions.

As the quintessential Renaissance man, Dada Vinci's interests knew no boundaries. He was also a limericist, a saguaro, a piñata, a chuckwalla and, during a brief phase in his life when he championed snotty little dancers, a twerpsichorean. Another time, he was so focused on making baskets, especially interweaving the flexible wooden strips, that acquaintances thought he'd developed a splint personality. Once his basketmaking interests waned, Dada Vinci turned to shipbuilding. Recalling the tragedy that befell nearby Pompeii when Mount Vesuvius went off, he was determined to build a vessel that could withstand the rigors of a volcanic eruption. However, the resulting "volcanoe" lasted only a few harrowing seconds after the molten lava lapped against its birch bark underpinnings.

During his later years, Dada Vinci's health declined, and he suffered from one viral infection after another. No matter he loaded up his body with plenty of vitamins C and, as suggested by a musician friend, C sharp, the chills, coughing and sneezing persisted. A doctor named Faustus who treated Leon was able to isolate the virus, though unable to cure him. He did, however, publish a paper on the infection, which he dubbed the Dada Vinci Cold.

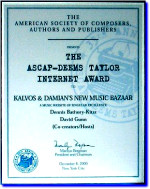

From cold to hot, that's how today's 528th episode of Kalvos & Damian's New Music Bazaar is apt to run. The outdoor thermometer, in no uncertain terms, says "hot;" the music inside, thanks to today's special guest composer, says "cool;" bridging the gap between the two can sometimes be accomplished by saying "Kalvos."

|